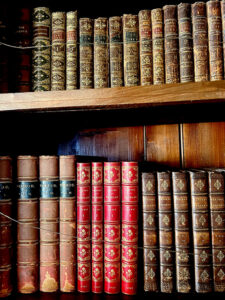

Boc

Boc

Just as I used to do on long past childhood walks with my family, I stop and stand still underneath the light filtered canopy of a huge tree and stare upwards. This view has always amazed me: the beauty and complexity of the arching grey branches and twigs, the muted colours and the gentle noise of the moving leaves above my head. Such old trees are majestical, they seem like nature’s cathedrals and never fail to make me feel both humbled and at peace.

The beech glades around me are rooted deep into the chalk soil. The trees have smooth

Just as I used to do on long past childhood walks with my family, I stop and stand still underneath the light filtered canopy of a huge tree and stare upwards. This view has always amazed me: the beauty and complexity of the arching grey branches and twigs, the muted colours and the gentle noise of the moving leaves above my head. Such old trees are majestical, they seem like nature’s cathedrals and never fail to make me feel both humbled and at peace.

The beech glades around me are rooted deep into the chalk soil. The trees have smooth bark and grow best in groups, liking each other’s company. Called the queen of British trees, they create a unique high leaf canopy. I have read that it used to be said that no harm could befall a traveller who was lost and sought shelter under the branches of a beech and equally that any prayers uttered under a beech would go straight to heaven. Certainly, talismans from beech wood were once carried to bring good luck and increase creative energy.

bark and grow best in groups, liking each other’s company. Called the queen of British trees, they create a unique high leaf canopy. I have read that it used to be said that no harm could befall a traveller who was lost and sought shelter under the branches of a beech and equally that any prayers uttered under a beech would go straight to heaven. Certainly, talismans from beech wood were once carried to bring good luck and increase creative energy.

The beech trees at Highclere tend to live for two to three hundred years and over their lifetime provide gnarled and knotted habitats for a lot of other wildlife. The foliage is eaten by caterpillars and the seeds provide foraging for small animals such as mice, and voles and birds. Around the base of some trees, natural small wells collect water from which the dogs love to drink - I imagine it must taste especially good.

In addition, native truffle fungi grow in beech woods. These are ectomycorrhizal, which means they help the beeches obtain nutrients in exchange for some of the sugar the tree produces through photosynthesis.

The beech trees at Highclere tend to live for two to three hundred years and over their lifetime provide gnarled and knotted habitats for a lot of other wildlife. The foliage is eaten by caterpillars and the seeds provide foraging for small animals such as mice, and voles and birds. Around the base of some trees, natural small wells collect water from which the dogs love to drink - I imagine it must taste especially good.

In addition, native truffle fungi grow in beech woods. These are ectomycorrhizal, which means they help the beeches obtain nutrients in exchange for some of the sugar the tree produces through photosynthesis. It is easy to find mosses and lichens in these woodlands and when these great trees eventually fall over, they contribute to the next cycle: the decaying trees and plants become soil for fungi beetles, insects, new plants and so on.

Beech wood is strong and resistant and has been used for generations for furniture,

cooking utensils, tool handles whilst the wood burns well and was traditionally used to smoke herring. The edible nuts, or masts, can be fed to pigs and I might collect some for our own. In the past our ancestors relied on “natural” wisdom culled from watching the flora and fauna around them. Where to find the best places to live based on good sources of fresh water, natural shelter and a learnt knowledge of the soil and land was carefully passed from generation to generation. Given how long Highclere has been inhabited, we clearly ticked all those boxes.

It is easy to find mosses and lichens in these woodlands and when these great trees eventually fall over, they contribute to the next cycle: the decaying trees and plants become soil for fungi beetles, insects, new plants and so on.

Beech wood is strong and resistant and has been used for generations for furniture,

cooking utensils, tool handles whilst the wood burns well and was traditionally used to smoke herring. The edible nuts, or masts, can be fed to pigs and I might collect some for our own. In the past our ancestors relied on “natural” wisdom culled from watching the flora and fauna around them. Where to find the best places to live based on good sources of fresh water, natural shelter and a learnt knowledge of the soil and land was carefully passed from generation to generation. Given how long Highclere has been inhabited, we clearly ticked all those boxes.

There is a general hope that the more we understand and love the natural world, the more we might lookafter it. The Anglo-Saxon word “boc” leads us both to the beech tree and to the word which later became “book” thus connecting, albeit tenuously and probably only as far as northern European languages go, trees with wisdom. In German certainly the word Buche and Buch could not demonstrate this link more closely.

There is a general hope that the more we understand and love the natural world, the more we might lookafter it. The Anglo-Saxon word “boc” leads us both to the beech tree and to the word which later became “book” thus connecting, albeit tenuously and probably only as far as northern European languages go, trees with wisdom. In German certainly the word Buche and Buch could not demonstrate this link more closely.

Personally, I also like to think the French word for beech, hêtre, is derived from hestre therefore linking it to “history”. In this way, trees become both our history and a narrative. We can write in our books and remember that protecting old, established woods and trees is essential and inextricably linked with wisdom. I, for one, find this highly satisfactory.

Personally, I also like to think the French word for beech, hêtre, is derived from hestre therefore linking it to “history”. In this way, trees become both our history and a narrative. We can write in our books and remember that protecting old, established woods and trees is essential and inextricably linked with wisdom. I, for one, find this highly satisfactory.

35 Comments

Good morning!

So much to ponder...

I'm transported to my childhood willow tree I loved to climb.

Trees and books are two of my favorite things.

Thank you for a peaceful beginning to the week.

Cheers

Shelley in Virginia

PS: I think your photos today would make very satisfying puzzles!

Thank you! These posts are uplifting and educational-really appreciate you for posting them.

Thankyou!

The wonders of nature never cease!

You do indeed have beautiful grounds to show off. I don't know whether you prefer a beech tree (the green-leaved version) or a copper beech? Either version has a smooth, attractive bark and much to admire. I remember the copper beech tree in the grounds of my school fifty years ago, which was very well loved by the pupils and alumni who remembered it in our alumni-newsletters.

I can never decide..

I lovely the picture of Boc did you and lord caravan have a nice weekend and lovely to visit highcelere castle and l am fan of Downton Abbey

I feel as though I can hear the leaves rustle overhead. As I read, I could feel myself longing for a good book under your lovely beeches. Thank you.

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

A most beautiful post to read to begin the week! We have several silver beech trees in our yard, and I, too, love to look up as the sunlight filters through the leaves and branches. When there is the slightest breeze, the light dances!

The language connection with beech and book and history is new to me, but makes perfect sense. You find endless ways to give us something new to examine, and historical perspective never ceases to amaze.

Please continue to be well and all good luck in the weeks ahead. I have so many happy memories of visits to Highclere and hope to return again!

Best regards,

Charlotte Merriam Cole

Thank you for your good wishes for the week ahead

Aboriginal proverb

"Look after the land and the land will look after you, destroy the land and it will destroy you."--

Donna

Toronto Canada

Beautiful!

I can’t wait to read your latest “boc” which I received on my visit to Highclere on Friday. The information on Egyptology that you imparted in your talk will linger long in my mind. May 12 is my daughter’s birthday and while I missed being with her, the day at Highclere was magical—and made even more so with the birth of your yellow lab Stella’s six puppies. When I rewatch a Downton Abbey episode that begins with the walk toward the Castle, I can say, “I did that.” Thank you.

Thank you - the famous walk you have now done!

Love the wonderful words and pictures to wake up to. Also love learning about the growing things across the pond.

Uplifting and educational. Thank you

Fondly Jenny

Lady Carnarvon, no more can be said by me, you said it all beautifully. Cheryl.

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Trees are one of the many things that amazed me during my trips to England. They were majestic. I hope one day I can sit under one of Beech trees at Highclere. Thank you for a beautiful post.

Susan

I hope so too

Lady Carnarvon, thank you for sharing your love of trees. I feel the same as you do, and am always much more at peace when surrounded by big beautiful trees. There’s something about the way they move in the wind and the sounds made by their leaves that almost makes me believe that they’re alive like the trees in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Anyway, I love trees! You are blessed to have such wonderful ancient trees and woods at Highclere. Thank you also for your observations on the connections between the trees and books as well as history. Food for thought indeed. Have a successful week. Suzanne in Georgia (U.S.)

I keep turning round the idea of connections in my head just now..

Lady Carnarvon,

Your story of the beech tree and its history led me to do some research this morning, as this tree is my favorite, and I was so caught up in your writing about this tree and its relationship to books, my other favorite.

I hope you don’t mind if I add a few things I learned, as I felt such a kindred spirit with you. I especially loved the following, describing the ‘fagus sylvatica’ or English beech, possibly found as early as 4000 BC in southeast England.

“The early Celts worshipped a beech god known as Fagus; the tree was believed to be a symbol of prosperity. The practice of tying wishing rods to a beech tree can be traced back to ancient Celtic customs, and a fallen branch would have wishes written on it, for consideration by the faerie queen.”

Finally, I found that the English beech is known as the “queen of trees,” and the mighty oak as the “king.” Glad to know trees also have royalty in dear England!

Thank you so much for another piece of English history. And enjoy your walks under these beautiful trees.

Martha G

I will enjoy my walks under the the beautiful trees!

Lady Carnarvon, trees are a sheer thing of beauty and the ones you have in the grounds of Highclere are something to behold, the sheer size and majesty of those trees is stunning. I have some bizarre love of trees and can lose myself in hours of photography in appreciation of our many different species, it the places and memories that they transport you too. I equally enjoy dead trees too as when left standing they create such beauty. We must look after our fabulous trees!

Samantha Warren - Redditch

I totally agree!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Very interesting reading. For your information I can inform that beech in Swedish is ”bok”, which goes both for the tree ”beech” and the ”book”.

Sincerely,

Håkan Brorson

Professor

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Lund University

Thank you for letting us all know!

Lady Carnarvon........The Beech tree in England as beautifully described reminds me of the sprawling oak trees here in the U.S. In there own way, the provide a feeling of strength, security, and calm. Thank you for reminding me of my childhood where I had a large oak tree outside my bedroom window. Are there any new restoration going on at Highclere?

There is always something - in fact quite a bit just now ...

I cannot wait to tour your peaceful world. Thank you for the most lovely thoughts about books and trees, both of which I cherish everyday. Inside my reading room are the treasures that I have yet to read while out through the encompassing windows I look upon a 20 ft. tall pecan tree that my dad planted when I was about 3or 4. I promised him that I was going to grow faster and taller than it would but of course that didn’t happen! Thank you.

How funny!

How beautiful and inspiring - gorgeous pictures too! I also love trees and this was a delight to read.

Thank you Lady C!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I bought my husband a two person hammock for his birthday, to place under a Canadian maple we have in our garden, so that he (and me when its either vacant or he budges up) can look up through the branches and admire the strength and glory of the canopy above. You are so right, those who love trees are naturally drawn to books. Summer finally appears to have arrived, and the trees are amazing,

Jane

What a lovely thought!

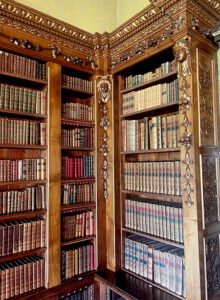

What a fabulous post! Surely that's an exquisite way to start the new week. Your description reminds me of the awesome trees near Highclere Church and the majestic books of the Library. They both share an important and historical past, a powerful present and a fascinating future. In fact books and nature are immortal.

We need to hang on to them

Lady Carnarvon,

During our trip to London last week for the Coronation, I found myself taking many pictures of trees along the Mall, at Green Park, at Hyde Park, at the cliffs of Dover, and at other locations. There are a great many stone monuments, but they do not compare to the majesty of trees and our connection to them.

I hope you had a happy mother's day Lady Carnarvon.

It is just a normal day here, our mother's day is in March - but thank you

My grandparents had a huge magnolia tree in their front yard I have great memories of being under the tree and looking up it was glorious great memories.

Lovely memory

Beautifully written. Safe travels to New York next month for the book signing; wish I could be at Barnes & Noble to meet you. Best wishes, Sandra

Thank you

Ma’am,

Really enjoyed looking at the carvings in the bookcases. So much detail in your life-amazing.

Holly

I feel our beautiful trees are a metaphor for life. Keep your roots firmly in the ground ,spread your arms to embrace the wonder of life ,and shelter your loved ones ,to keep safe under the warmth of the canopy We learn so much from the bounty of Nature.

I was so lucky to be on your gardens today - what a treat.

Thank you.

I stood under the very tree in your photo and thought it would be a perfect place to lay underneath and day dream or meditate wish I had done so♥️

Love from Bermuda Gal

You will have to return!

As a child, I knew every climbing tree in my neighborhood. They all had different characters and characteristics, and I had named each one. Nothing feels more peaceful than being rocked by a breeze among the shimmering leaves and cradling branches of a tree ‘friend’ on a summer afternoon. Here’s to climbing trees and reading books — two of my favorite childhood pastimes! Of course, the book habit continues now that I’m all grown up. And I still love trees, albeit from the ground rather than among the branches these days.

What a lovely habit reading books!

Lovely picture of boc lovely to visit highcelere castle l am fan of Downton Abbey

Nothing is better than nature!

Lady Carnarvon,

I always learn something new from your writings. The pictures of the green fields at Highclere are do soothing and calming.. it is like the frame to a beautiful painting.

Thank you

Dearborn Lady Carnarvon:

Thank you for this Monday's blog.

Quite an article and something to think about. Very color rich picture of the Boc and the Library and it's books. If there were only more hours in a day so that I could read more.

I have just returned from a week's long business/pleasure stay in Seattle, Washington (a/k/a " The Emerald City) . This nickname has been given due to the lush greenery and trees that surround the area. I definitely can relate to the look up and wander and wonder as I walked under the beech and pine trees. Found my experience very peaceful and relaxing.

So until next week, keep gazing upward.

Perpetua Crawford

SANDRIA MADDOCKS May 14, 2023 at 10:20

Good Morning Lady Carnarvon,

My husband and I recently had the pleasure of visiting Highclear Castle and thoroughly enjoyed this wonderful place. I have longed to visit since before lockdown and have been patiently waiting for the opportunity. I loved the beautiful pietra dura table in the smoking room and the Egyptian museum. I visited Cairo museum some years ago and thought yours was better, more compact! but just as beautiful.

It was such a pleasure to receive your book, Lady Almina, thank you so much. I have just finished reading it and found it so interesting. What a woman she was, she did so much for the castle and the patients and everyone. My grandaughter (Evie aged 10) has been learning about Tutankhamun, Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter at school for the 100th anniversary, she is now quite an expert, it fascinates her, so I have given her one of the Lady Almina books and she has claimed the Egyptian museum book.

Thank you once again for the lovely books and for the wonderful day at the castle.

Our very best wishes to you and everyone at Highclere.

Sandria and Alan Maddocks of Derby

Leave a Comment

- Christmas

- Community

- Dogs & Horses

- Egypt & Tutankhamun

- Entertaining

- Farm

- Filming

- Gardens

- History & Heritage

- Daily Life

- Royalty

- Cooking

- Interiors

- Heroes

- Architecture

- Cars

- Conservation

- Downton Abbey

- Events

- Gardens & Landscape

- Highclere Castle Gin

- History

- Planes

- Restoration

- Stories & Books

- Uncategorized

- Visitors

- Wildlife

What a lovely post to read first thing on a gloomy, Monday morning. Thank you for sharing.

I agree wholeheartedly and envy you home library!

Renee Garrison, President

Florida Authors and Publishers Association

A nice Monday morning read. Great bookcases!