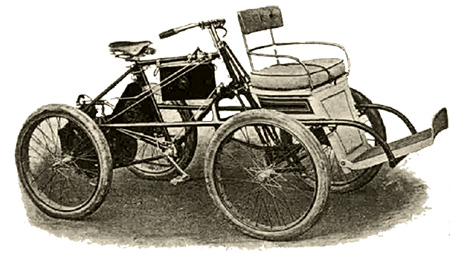

Some 120 years ago the first few cars began to be seen on roads here in the UK. Noisy metal boxes on wheels, they were deemed strange and dangerous contraptions so much so that at first, they had to be preceded by somebody walking in front of them waving a red flag. As most people still relied on horses for transport, the words and terminology of carriages were transferred to the new machines – horsepower, landau, brougham, phaeton undercarriage and so on.

Some 120 years ago the first few cars began to be seen on roads here in the UK. Noisy metal boxes on wheels, they were deemed strange and dangerous contraptions so much so that at first, they had to be preceded by somebody walking in front of them waving a red flag. As most people still relied on horses for transport, the words and terminology of carriages were transferred to the new machines – horsepower, landau, brougham, phaeton undercarriage and so on.

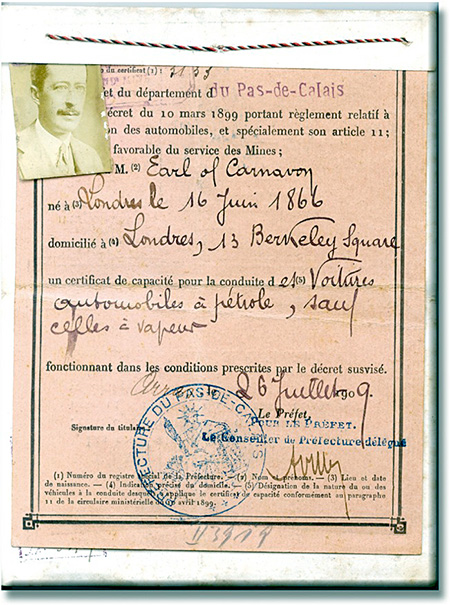

Lord Carnarvon was one of the first to own a motor car having been intrigued by them from the start. Given their unreliability, he always drove with Trotman his chauffeur who was also a mechanic. His father-in-law, Alfred de Rothschild, went one step further. He was driven in one car which was followed by a spare car plus a third vehicle containing his mechanics and spare parts for most eventualities. These precautions were vital for a smooth journey as there were no garages, no AA or rescue services and places to purchase petrol were few and far between. The tyres were a particular problem and often got punctures not least from the horse-shoe nails which were everywhere.

At the time, it was not a given that cars would be powered by the internal combustion engine. The Wankel engine had practical credentials and steam engines were better understood. In fact, Lord Carnarvon had previously invested in a local enterprise to build cars with steam engines here at Highclere. Steam cars were faster and, as with the electric cars which were also being developed, needed no gearbox due to their torque delivery. The downside was that they had to stop for water every 30 miles.

At the time, it was not a given that cars would be powered by the internal combustion engine. The Wankel engine had practical credentials and steam engines were better understood. In fact, Lord Carnarvon had previously invested in a local enterprise to build cars with steam engines here at Highclere. Steam cars were faster and, as with the electric cars which were also being developed, needed no gearbox due to their torque delivery. The downside was that they had to stop for water every 30 miles.

Early motor vehicles relied on gravity to persuade the fuel to flow to the carburettor. As a result, and depending on the position of the fuel tank, if it was only half full, ascending a steep hill with a tank less than half full might mean reverse was the only option. Driving was always an adventure.

As there were only a few such machines, each car was closely observed by a fascinated and often disapproving audience. However, they were here to stay. In a remarkably short time, the square boxes changed shape, acquiring longer and sleeker silhouettes, varied colours, windscreens and leather and burnished wood interiors. Gradually more economic models were developed which returned to simpler shapes designed to convey families on picnics or commuters to work.

As there were only a few such machines, each car was closely observed by a fascinated and often disapproving audience. However, they were here to stay. In a remarkably short time, the square boxes changed shape, acquiring longer and sleeker silhouettes, varied colours, windscreens and leather and burnished wood interiors. Gradually more economic models were developed which returned to simpler shapes designed to convey families on picnics or commuters to work.

Roads and tyres naturally developed just as quickly and within a few decades a way of life and ability to travel which had been part of human life for millennia fundamentally changed.

Some things don’t alter however and the state of the roads and permitted speeds on them remain a point of contention. Given the overwhelming number and congestion of cars, speed limits which initially increased have these days often been reduced. The speeding fines and points on his license that the 5th Earl accrued for travelling at 25mph through Newbury in a 20mph zone are instantly recognisable to the modern driver.

When I was writing my latest book about the 5th Earl, one method I used to trace his movements was through the records of his speeding tickets. He began to acquire them almost as soon as he bought his first car and, although he was always apologetic to the courts, he also always engaged a barrister to try to keep himself on the road. He certainly didn’t want to lose his license.

Many of the stories are quite funny. There were no speed guns so careful policeman had to try to gauge a potential miscreant’s speed by timing the vehicle through two measuring “posts”, often trees on the side of the road. (Speed equals distance divided by time). At one court case, the policeman commented disapprovingly that Lord Carnarvon and the lady he was driving (his wife Almina) “disappeared in a cloud of dust”.

Despite her husband’s enthusiasm Almina tended to travel by train on longer excursions as there was more room for her luggage – the cars were always full of spare parts and she was not a lady who believed in travelling light. For my own part, I am more likely to have a boot full of Labradors as I dash round the estate looking at various crises and problems or, if I am particularly lucky, a new walk to explore.

Instagram

Instagram

What a delightful perspective on both a personal and global history! I can picture the 5th Earl racing across the countryside with far more humor than I view speeders today.

Lovely picture of in the Beginning and did you and lord Carnarvon have a nice weekend and lovely to visit Highcelere castle and l am fan of Downton Abbey

Oh that is so interesting! The thought of a new walk to explore sounds exciting. I wish you a wonderful May!

Thank you!

I’m a lover of cars, thank you for the information on Lord Carnarvon’s cars.

fondly Jenny

I feel like I was just transported in time in one of the new automobiles. The 5th Earl really lived an extraordinary life. How luck for us that you and your husband are willing to share the plethora of information and stories.

Thank you!

Kathy

Loving the post on the new litter of puppies. So cute.

They are so cute!

Thank you for your interest

So enjoyed today’s blog!

Thank you

Another interesting historical blog again Lady Carnarvon,

Impressive that so many photos and paperwork as been saved by all Lord Carnarvons & their Lady’s over all these years and how you are adding to it all! Educational and entertaining, Thank you again.

I adore today’s entry. I have been engaging in a lot of my own geological research, and it is amazing the research tools we use to learn more about our family. I would have never thought to look at speeding tickets! How creative.

I loved your book about Almina. One of my favorites to date. Thanks for all you do!

Annie Migdal

St. Louis, MO

Glad I have given you a new angle to research

The conversational topic of “the conditions of the road”

we think of as bland these days. Heavens what they must have been before bituminous paving arrived… The lost yet very obvious , detail of shed “shoe nails” yikes- a wonder anyone ever drove at all. Does make having a mechanic n parts available essential…

Thank you for the snip of early motoring… regards

elizabeth h

Thank you for reading the blog

Very kind and I hope you might try the Earl and Pharaoh book next!

Research leads in such unexpected ways!

Lady Carnarvon,

What a story! I smiled as I read it, thinking about the trials and tribulations of those trying to give the traveling public “new” and “exciting” cars! I may not live to see these new things on our roads in great numbers. Just as well! I don’t want to be run down by a car with no driver.

I hope you find a new path for me and the sweet puppies!

Martha G

I think I will write next week about them..

We have certainly come a long way. A gentleman just recd a ticket for doing 400 K on the Autobahn! Judge found he was not guilty since there is no speed limit on the autobahn.

Very interesting blog this sunny Monday, but to get a good understanding of those “horsepower” engines and machines, I had to go to my “translate” English to English:

So, your lab doggies can fit in a “boot” and not a “trunk”? And do you pick up the “bonnet” or the “hood” to see if you are in need of oil? And fill-‘er-up with “petrol” or “gas” …too much fun! But enjoy a nice drive around the Highclere Castle grounds with a clean “windscreen”, (or as I know it as a “windshield”! ) Many thanks for this lovely tale.

Very funny!

I looked all over for the labs when I was there last week and was thrilled to learn that Stella had given birth that day. Perhaps a puppy blog could be considered for the near future?

Funnily enough that might just be coming up!

To lady carnavon

We had the pleasure of visiting you at the Castle of Highclere on April 30th and the reception of the personel as well as the magic to be done during this visit .

We wish to inform you that this visit is etched in our memory for the rest of our lives.

Your book “chrismast Highclere” has been appreciated

Your domain is sublime!

I have been receiving your blog for several years

Congratulations to the whole team for this unforgettable visit

Best regards

Louise and Guy

Lovely compliment thank you!

Quelle histoire passionnante, vous avez le talent de rendre les choses encore plus intéressantes,lady Carnarvon

Merci

Dear Lay Carnarvon,

Your story of cars and clouds of dust, and policemen counting trees or pots to decide “how far” cars used to go are lovely and funny. What a different world! you made me laugh and really enjoy the beginning of this week. And the pictures are lovely too! Thank you!

Enjoy the rest of your week!

Wonderful article! I learned so much!!!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

such an interesting story! I have just bought my first electric car, a Mini, which doesn’t have a great range on it and a boot just about big enough for a handbag, so as with all good dog lovers, I have kept my old beloved Disco just for them and for longer trips. The thought of not being able to get to Highclere or the Quantocks with the dogs, is quite horrifying, but going to the shops and to work is now in the green machine pocket rocket. The car evolution continues..

Jane

Your articles are always written so realistically. I feel like I stepped back in time. Those cars were true works of art.

Good day, Do you have any of the early car about? This has been a fun topic to read. Thank you so much for sharing .

Dear Lady Carnarvon……..Your posting today was so enjoyable to read. Maybe that was the inspiration for Mr Fellows to make Edith “a speed fiend” in Downton Abbey. Its fun to look back and see things how they began and where they are now. Thank you for the wonderful pictures and documents.

Thank you very much

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I really enjoyed reading your post about cars. I agree, driving with dogs is a pleasure. I love seeing their heads in my side view mirrors.

I also would like to share with you, that it was a pleasure to visit Highclare Castle on April 19th. We’ve even exchanged a glance while your pictures have been taken outside, I’m sure you don’t remember me, but I will never forget you. And please allow me to say your hair looked divine.

Twenty four hours before I left my current house in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, crossed the border to United States, drove four hours to Austin, Texas, where I took a direct flight to London, my friend picked me up at the Heathrow and straight from the airport we arrive to your place. Thank you for opening your home for us and I’m sending you my best wishes back from Mexico.

Thank you for visiting Highclere and so pleased you enjoyed your visit

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I would be like Lady Almina and take the train. I would think it would be move comfortable. Great photos of the old cars. Again a great post. Thank you.

Susan

Oh I do driving abd there is nothing better than a boot full of Labradors ❤️!

On another note – super-excitibg “news” here today re a “new’ Dowton … I do hope so .

Oh I do ❤️ driving and there is nothing better than a boot full of Labradors ❤️.

On another note, very exciting news here today on a possible new Downton….. I do hope so !

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I see you mentioned the Belgian Metallurgique car above. How ever i think the pictured car is not the Metallurgique. Of 1908 those cars had a verry particular v shaped radiator. I do own a 1910 model and would love to send you a photo if i had a mail adres.

Verry kind greetings from Belgium.

P.s. Hope to see more photos of the 60 cars of the collection.

It was not the same car – just a photo from the archives as sadly I have known of the Belgian Metallurgique – I would love a photo – Highclere Castle, Newbury RG20 9RN

Very interesting article! I particularly noted the excess of horse shoe nails causing tire punctures. I have had several tire punctures due to roofing nails from a careless contractors truck. Some things never change.

Also, the modern-day police here use two fixed points as a back up if their radar isn’t working, or if it’s preferable given the terrain. Thank you and have a lovely rest of May!

I had a flat tyre on Saturday – very boring

Very interesting! The pictures are great. Some of the cars from the 1920’s and 30’s look so nice but not terribly safe. The ones from the very early 1900’s look rather fragile. No wonder the Earl drove around with extra car parts and his mechanic. I had no idea that steam powered cars had been developed. Wouldn’t it have been good if those electric cars had been the front runner ? No need for gas /oil. How different things might have been.

I think we are catching up!

Lady Carnarvon,

As usual, I love how you bring history to life! Your paintbrush with words is so amazing, I can see the events taking place as I read. The fifth Earl was quite a character with the most extraordinary sense of adventure. Through your books, I feel as though I know him.

Cannot wait to hear more about the new Downton???!! Fantastic!!

Happy spring to you all,

Patsy

The sun is shining at last !!

Lady Carnarvon,

I couldn’t help but notice the beautiful script on the documents, perhaps because I taught cursive writing in school. I find it sad that many US schools do not even teach students handwriting. Thank you for this peek into Lord Carnarvon’s love of speed!

I feel sad too!

I do enjoy your writing and your podcasts

The “cars” of your photographs are so special and lovely. Surely Tom Branson would love them! Have a beautiful week!

that was a fun story line …

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you for the interesting story on the early automobile and ownership of automobiles by the family. I enjoyed the stories.

Thank you!

As I read your fun description of Lord Carnarvon motoring, above speed limit, over the county side, somehow it brings to mind the story of Toad of Toad Hall. In the best possible way, of course!

How in the world did i miss a photo of new puppies?

Could you post the pics again somewhere? puh leeze??

I am posting regular ‘Pup Dates’ on my Instagram

Good morning, from Windermere, Florida. I’m thoroughly enjoying your new book, Lady Fiona, and just got to the Chapter on the Earl getting into horses and cars. He truly must have been an interesting fellow.

Love from the USA,

Peggy Helbling

It always amazes me how things have changed in the past 100-plus years. From horse-and-buggy to space flights. My father died in 2018 at the ripe-old age of 92. He was born in 1926 during the Great Depression in rural Georgia (America not the country). At the end of his life, he was paying his bills online.

I so enjoy your books on Highclere’s history. I can’t wait to read your latest.

As usual, another delightful story.

Thank you,

Amy

Dear Lady Carnarvon:

Thank you for this Monday’s blog and for sharing the brief local history of the automobile.

I really like the photographs of the old cars. You are very fortunate that so many records have been preserved for quick reference.

I found the comment about a policeman having to gauge the speed at which the driver was going comical.

I can empathize with any driver from the last century, as the roads were in deplorable condition then. Oddly, the roads in Michigan are always under such circumstances and are in a constant maintenance mode (a/k/a orange barrel season). Even though there are no horseshoe nails lying around, I still managed to receive several flat tires from construction nails that had been picked up while travelling around town.

At the moment, I have no interest in an all-electric vehicle; just a hybrid until all the “kinks” for recharging and the range for miles driven greatly improves.

Until next time, may you and your Labradors enjoy the rest of the week.

Perpetua Crawford

Guess that’s why “ Branson” was the chauffeur…. … he was a good car mechanic.

Loved this story.

Rosemary

PS. Looking forward to your next book!

I just finished reading The Earl and the Pharoah and enjoyed reading all about the escapades while the Earl was driving . He was ahead of his time.

What a fascinating life

Hi

My mum’s friend Grace Becker nee Trotman is staying with me in Reading and is curious to meet up.

Dulcie

Thank you for the interesting insights to a car owner at this time.