Looking around the Smoking Room, your gaze may be held by some of the paintings in beautiful carved frames or instead settle on the huge leather sofas and large rug. Pause long enough though and you might notice some exceptional clocks on the mantleshelf. With its warm terracotta walls, the room is quietly inviting, asking you to take some time out and admire works crafted to the highest standards in past times. It is a room designed to give a sense of relaxed opulence with perhaps a slightly masculine bias. Somewhere to hide out, indulge in some quiet conversation or simply read a paper without interruption. It is a world of quiet and unobtrusive luxury.

Looking around the Smoking Room, your gaze may be held by some of the paintings in beautiful carved frames or instead settle on the huge leather sofas and large rug. Pause long enough though and you might notice some exceptional clocks on the mantleshelf. With its warm terracotta walls, the room is quietly inviting, asking you to take some time out and admire works crafted to the highest standards in past times. It is a room designed to give a sense of relaxed opulence with perhaps a slightly masculine bias. Somewhere to hide out, indulge in some quiet conversation or simply read a paper without interruption. It is a world of quiet and unobtrusive luxury.

Watches, cars, views from hotels, infinite sandy beaches, polo ponies, immaculate tablescapes and oversized sunglasses. These are just a few examples of items that are often beautifully photographed and choreographed in advertisements designed to symbolise worlds of luxury for us to admire and buy into. The adverts promote comfortable moments of utter idleness as if merely buying the items concerned will give you this life style.

Despite the magazines, in reality, the moments of idleness we have all experienced over the last 18 months have felt far from luxurious, with the twin realities that very little was actually possible in lockdown and, in any case, for most of us such things are an aspirational fantasy rather than a potential reality. Thinking about it, in essence many of the goods thus advertised are everyday items – food, clothing and holidays – but elevated to luxury level by detail, depth of fabric, limited access, available leisure time and, of course, price.

The word luxury has assorted associations depending on how kind you are feeling, from a suggestion of excess and self-indulgence to a sense of refinement, self-reward and pleasure. It doesn’t just have to be about money either but can include environmental and cultural awareness such as choosing to buy free range eggs or organic homemade sourdough bread.

The word luxury has assorted associations depending on how kind you are feeling, from a suggestion of excess and self-indulgence to a sense of refinement, self-reward and pleasure. It doesn’t just have to be about money either but can include environmental and cultural awareness such as choosing to buy free range eggs or organic homemade sourdough bread.

Socrates wrote that in a good state “families do not exceed their means; having an eye to poverty or war … And with such a diet they may be expected to live in peace and health to a good old age, and bequeath a similar life to their children after them”. This may be very admirable, not to mention sound economic sense, yet I cannot help thinking that I agree more with Winnie the Pooh: “the things that make me different are the things that make me me.” Thus, I like to reposition the association of luxury to something special, something that is beyond an everyday necessity but which is also achievable.

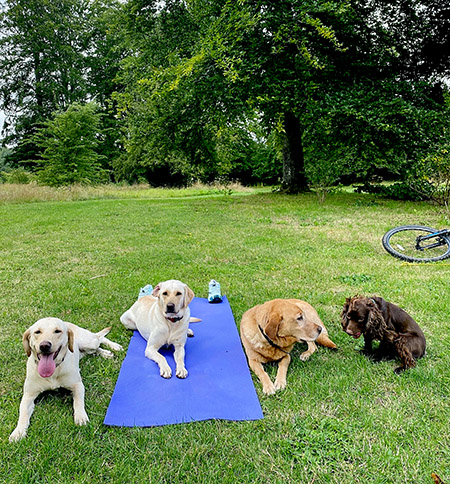

We all have our own idea of what constitutes luxury. For one girlfriend it is a pair of top of the range Wellington boots, dogs to walk and muddy paths to explore. For another it is a really indulgent afternoon tea with her daughters, or for others just a good night’s sleep.

Furthermore, the idea of luxury changes over time – the luxury of childhood was being encouraged to read, play sports, to be independent, to climb trees or hunt shrimps in the rock pools, spending time in the country, looking at trees to estimate points of the compass and counting magpies to avoid bad luck. Going abroad was a luxury, not a given, and going to a restaurant was a treat. Looking back, today I think that being able to grow up in that environment was in itself a luxury: a luxury of time, space and freedom.

Ironically, it was Christian Dior, one of the most quintessential purveyors of luxury items, who summed it up the best when he said: “I believe that in it there’s something essential. Everything that goes beyond the simple fact of food, clothing and shelter is luxury; the civilization we defend is luxury.”

Ironically, it was Christian Dior, one of the most quintessential purveyors of luxury items, who summed it up the best when he said: “I believe that in it there’s something essential. Everything that goes beyond the simple fact of food, clothing and shelter is luxury; the civilization we defend is luxury.”

For myself, it is going for a walk, doing some yoga, picking flowers or sharing a simple supper outside and catching up. Also, I would really like to go on holiday, to see other places and hear other voices, to be curious. That I think that is rapidly becoming less of a luxury and more of an essential!

.

Instagram

Instagram

How true. We each have our own ideas of what constitutes a ‘luxury’. For me it is having an extra half-hour in bed, when the day ahead is less busy than usual. At age 72, I feel I’ve earned it!

Excellent idea!

So well said. Your thoughts and words have really hit home about what true luxury is. ❤️

How can three american woman get tickets two one of your events the living in a castle, it wont go through with the sage pay can you help and it wont take our credit cards please help. Debra Kunz

Debra – I have asked the office ladies to email you and help you with the tickets

True luxury is a life that people who are only rich most despise, in that it cannot be bought with money. It is a life of character and personal sovereignty, where time is spent doing what one pleases to do, not what one is forced to do, to meet the pressures wrought from expensive trinkets.

Lady Carnarvon pictures of Luxury and highcelere castle and did you have a lovely weekend lovely to visit highcelere castle

Hello Lady Carnarvon

For some, luxury means much more. Consider all the support Highclere provides for the many charities you support in many ways. By doing this, those with disabilities etc are able to experience a better quality of life that otherwise would not be possible without your continued financial support.

Then Buy Gin, Support Highclere is another issue.

Carry on Highclere. I still have to make a donation to SSAFA by not buying a Highclere Churchill cigar.

Astute observations. Thanks you. And , I love the pups cooling off in the water trough!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Another wonderful piece!! Yes, luxury means different things at different stages of life.

Lockdown has made us all reevaluate what true luxury is, and for me, dreaming of the world returning to a safe new normal feels like a luxury! Love your beautiful photographs of the Castle, the dogs, the horses and the gorgeous landscapes. I truly hope to return when allowed from the US, and what a luxury that will be!!

Thank you and please stay safe and well,

Best regards,

Charlotte Merriam Cole

I look forward to your return!

Thank you for sharing your beautiful home, very inspiring.

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

free time for me is the biggest luxury, and being free to be able to chose what I do with it, a luxury that is sadly being denied to so many people around the world. Christian Dior gave us luxury clothing and perfumes, Catherine Dior the freedom in which to enjoy it, one of the bravest women in WWII in the French resistance. That plus Labradors and Lurchers, and good food and wine.

Jane

Lovely Monday Blog again Lady Carnarvon.

Love the photos with the dogs again they actually made me chuckle when I first saw read across them.

It is interesting how the definition of “luxury” changes over time and given current circumstances. Especially during this challenging pandemic.

Thank you again for a joyful and uplifting read this morning. Heading out on a luxury activity of a walk-about now. Continue to take care and remain well.

Love these morning readings. Always a great way to start the day. Dogs are a happy added bonus!

Thank you!

Thank you for taking time to prepare such interesting, informative, and beautiful pictures in your blogs. I so look forward to your posts!

One day, I will visit 🙂

I agree with you about the carefree and simplicity of childhood, and travel now as an adult. I appreciate Dior’s quote. Thank you, Lady Carnarvon, for your shared reflections and the reflections you’ve stirred up within us.

Blessings from across the “pond”.

Lady Carnarvon lovely pictures of luxury and lovely to highcelere castle

The simple pleasures, the most luxurious…..

Connecting with the natural world, watching a baby laugh, eating spaghetti and meatballs!

Thank you so much for such a sensitively written piece. Your words stopped me in my tracks and I started thinking about the idea of the word luxury, which because of your piece, had me rethink it all over again. You’ve made my day; a day of introspection.

Diane, I totally agree and second your lovely comment.

Fabulous Blog Lady F

Cheers from Australia

When I was younger, much younger, luxury to me was going into a department store and purchasing an item without looking at the price tag. How I envied people who could do that! But as we mature our idea of luxury matures with us. I no longer envy people who can do that, but rather I bless them that they have been blessed. Luxury to me now is having lunch with friends who are still alive. It is being able to pick up and drive a thousand miles to see my grandchildren. It is the freedom to come and go as I please without restraint of any kind. It is sitting on a grassy Hill overlooking a lake and thanking God Almighty for the beauty that he has created and has allowed me to experience. A luxury is anyting that rocks my world in any positive manner.

Good afternoon, thank you for another installment of wisdom. If only more people shared your way of thinking what a wonderful world this would be.

Thank you

Dear Lady Carnarvon

Your writings on luxury were somehow restful to read. I have one more day left after today of being on holiday. Due to the circumstances of our shared global pandemic, it was another “staycation”, yet luxury in itself to enjoy the Delaware Beaches where we live – the boardwalk, a visit to the wild horses of Assateague Island just to our south, a round of golf with my husband and a couple if friends (them with their clubs, me with me canera), a wee bit of VAT-free shopping at out outlets. The best luxury for a frustrated, exhausted healthcare worker (I’m a Microbiologist doing, among many other usual tests, COVID testing) was glorious rest – time with my husband and out three Shektland Sheepdogs. Your article was well-timed as it gave me a deeper appreciation of the past dozen days and relaxed me as I began to feel the tense anxiety of returning to work. And so I thank you for this and your many articles which have provided me with much needed brief escapes.

Wishing you all the best!

Lois Timlin

Thank you

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

You are so right! For me luxury is to be able to have the time, space and will to do something that really makes you HAPPY, whatever that might be. For some, like me, cooking and watching nice films and series and, of course, when we can, going out with some friends to a lovely restaurant to eat something delicious and different. But to travel, these days, is difficult. Just to think that in long flights when you have to sleep on the plane, you have to wear a mask, is too much for me! with people coughing around you. No thanks! So, for the moment, abroad is just something that I can enjoy in the many platforms in social media, documentaries, etc. The world is all there for us to enjoy, even at a distance. Time will come when travels will be again what they used to be.

Glad to see that it’s not just my Labrador that indulges in a horse trough dip! More chance of keeping a hippo out of water than her lol

I’m glad I’m not the only person who noticed the doggo taking a dip in the trough! He seems quite contented!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Luxury to me is a cool September morning such as today, off work for the holiday and heading to the garden to pick tomatoes, peppers and figs! Enjoy your Monday!

Robert

Enjoy your day!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts and of course, your home. I especially LOVE the interaction you have with your dogs. Did a double take when I saw one of them resting in the trough. Definitely their happy place. Hopefully, one day soon, I will travel from our home in northern Ontario to Highclere.

Good morning from Maine!

Traveling is a luxury that I greatly miss. We had the pleasure of coming to Highclere in 2018 and got to chat with you for a few moments at the start of our tour. Exploring the gardens following the tour was magical. We spent a few hours taking in the sights and sounds of nature that surround the estate. We had plans to come back last year, but we all know how that went. Memories of that trip and hopes of future trips will see us through until we can get back to the UK.

Thanks for your blog!

Hopefully see you soon!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

The word luxury surly can be used to describe so many things, ideas and places. I am blessed and will have the luxury of spending time with very good friends this coming weekend. A long overdue girls’ weekend.

I so enjoy your weekly blog.

Thanks you,

Pam

Enjoy your girls weekend!

Hello from Fort Worth, Texas! My Monday luxury is sitting in my comfy chair with two fat cats in my lap, still in my pajamas, reading about your experiences and life, your thoughts and beliefs, while drinking an ice cold Dr Pepper soda. Dust bunnies and cat hair everywhere, droopy flowers needing watering, stacks of laundry, dishes in the sink…all this will have to wait while I travel to Highclere and visit with you every Monday morning. You put a smile in my life. Thank you.

I had to chuckle when I saw your dog in the trough. To a dog on a hot day, that is luxury! Thank you for your wonderful posts. I look forward to them weekly. God bless!

I have two parts of the year I call “the crazy times.” They are August, September and October, the beginning of the school year and April, May, June, the end if the school year. This year is even more crazy as I have volunteered to be an election courier for our upcoming September 14th special election here in California. This is a 16 day period in which certified couriers pick up ballots at designated places and bring them to the collection location. Although not a difficult assignment, it is a 4:00 pm duty each day and is a 60 mile round trip drive. Today, Labor Day in the US, will be an easy trip as it is a holiday. Tomorrow, however, will my first trip during rush hour traffic. As a school teacher, I have gotten up early every day for 45+ years. During those years, I have chosen to get up an hour early each day to read the morning paper. It is my favorite hour of the day, a chance to read and absorb the news of the day while drinking many, many cups of coffee. It is the luxury of time I have given myself.

You must be blessed with masses of energy? It sounds like you have no plans to wind down….

For me, luxury means going to Starbucks with my husband for a mocha and going back to England. Also I want to take him sailing to Greece.

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Once again I thank you so very much for a beautifully written & illustrated blog, your photographs are wonderful – especially of your Labradors IN the water trough – typical Labbies!!

My idea of luxury these days is a car to take me to the shops, or the coast, or indeed to Highclere! Since I broke my neck 3 years ago I have a lovely Mobility Scooter to get about on, but it confines me to just around the town, & the offer of an “Outing” further afield is a true luxury for me!

Have a wonderful Autumn my dear Ladyship, & I wish you & everyone @ beautiful Highclere a safe & happy September,

Love from Caroline x

Having just finished watching, again, the series Upstairs Downstairs, your essay speaks to the theme. When I saw your title I immediately wanted to read what you wrote. Luxury is uncommon and a bit of a mystery. Like your castle. A belonging. Mr. Hudson had a foot in both worlds but really didn’t belong in luxury. And glad of it in his way. It’s an interest subject.

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Luxury can be a much anticipated beach vacation or traveling to faraway places such as Highclere for the very first time. Now, that would be a real adventure for someone my age who has never traveled abroad! I agree with your association of luxury with something special, beyond necessity but also achievable. We all need something special for which to aspire and to realize that another world does exist beyond our own.

Fondly, Sandra

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

At this point, a luxury to me would be a day free of stress and worrying about the world as it is.

Thank you for sharing your beautiful home. I hope to visit it in the near future from the USA.

Another wonderful piece.

Lady Carnarvon,

I so agree with Gloria – the first response – an extra half-hour’s sleep, or today, and HOUR, on our US Labor Day! So thankful that I’ve lived a life of luxury – no serious illnesses, always able to pay my bills, able to have food to enjoy, and (non-Dior) clothes to wear! And the greatest luxury of the lives my husband, 80, and I at 78 live now is being in a retirement community with so many wonderful new friends! Some liken it to a luxury cruise – I liken it to living at Highclere Castle. We visited in 2013 and I remember the Smoking Room as well as the rest of the home and grounds in my mind’s eye. Thank you for this marvelous gift. I look forward to every Monday morning.

Martha G

Thank you!

Dear Lady Carnarvon

Thank you again for a lovely Blog. It would be nice to see the rooms of your home once passage is safe. Although my Physician was straight forward saying once you get booster shot just go!

That picture of the doggie in the tub is hysterical! He/She is in the lap of luxury!!! I know the feeling of getting out to travel – We are finally leaving home and taking a trip back East, albeit for a memorial service, but will be with lifelong friends. Hope you can get out of Highclere and travel somewhere soon! Take care, Chrissy

Luxury means something to everyone but simple pleasures are definitely the best. Love the photos of the dogs and castle. Luxury for me is skiing on beautiful Whistler Blackcomb mountains in Canada. Looking forward to visiting Highclere for the Christmas fayre on 8th December too.

Wonderful!

Thank you for an inciteful piece my Lady. September for us is a special month,our wedding anniversary is in the middle and luxury for us is taking time to be together, long walks,good food and as much peace as we can find . Simple things really but priceless I believe. Thank you again.

You mentioned clocks plural on the mantle in the smoking room.

I only saw one clock.

I love your Monday morning news!

Sandie Whitefish Montana

Thank you for discussing ‘luxury’ which is a very slippery word, indeed. Redefining or updating it could be useful by saying, as you do, that what we individually enjoy in terrms of an innocent pleasure is our own tailored “luxury”.

Latin had two similar words with overlapping meanings: luxus, meaning “luxury” or “excess,” and luxuria, which meant “rankness” or “offensiveness.” These terms became ‘luxe’ and ‘luxure’ in French, with meanings that preserved the distinctions of the original Latin. By the Elizabethan period, it was associated with adultery, as in Shakespeare (Hamlet) The French ‘de luxe’, meaning “of luxury,” became the English word deluxe. Over time, luxury came to mean a “sumptuous environment,” referring to food, clothes, and opulent lifestyle, as in the phrase “they lived in luxury.” This link with wealth led to the word’s most recent meaning, the one that refers to something nonessential or indulgent, an extra that is a welcome change that is not always there in regular life, such as “going out to a play was a rare luxury for them.”

For me, luxury still has strong connotations with fluffy towels, fine grand pianos, cut glass, velvet cushions and silver candlesticks. But since I have also worked for decades with a disability non- stop, time and health are definitely my luxury especially when combined with the capability to tour and get ideas from great houses and gardens albeit in a (new to me) camper van.

You did it again; taking a word and elaborating on it in an essay to give readers pleasure as well as something to think about. Your pictures always add that little something that can be delightful, beautiful or just memorable. Today your dogs amused me and the smoking room picture took me to thinking about the art at Highclere. Did I spy a Canaletto (or two or three)? Thank you for adding pleasure to my Monday morning routine each week.

I always follow Martha Glass in “comments” and now see that she is my contemporary. I am a bit older but close enough. One of my dearest friends had the same name so I always pause at her comments. You have opened up new friends from all over our countries of the like-minded. I must share that we in Louisiana have just experienced another blow….literally and figuratively. Just last Sunday Hurricane Ida hit. It was the most severe since the 1800s surpassing Katrina. Without power for almost a week, loss of 9 lives, trees and homes but, for survivors, renewed gratefulness for partial normality. We have no gasoline to move around because of many factors and grocery stores are low on supplies because we are cut off from normal transportation of goods. We have peanut butter and apples. My husband even had a cornea transplant the day after the storm…how that miracle was completed we are afraid to even ask. “Even So”……a lovely song expresses what we have no words to express.

Loved the dog in the water trough. Thank you for these wonderful insights into Highclere.

Thank you and glad to hear you have made it through “Ida” From afar it looked as if the levees held better

Lady Carnarvon,

I devour all your blogposts and photos about and of Highclere.

However, perhaps today’s edition had the perfect photo to illustrate the topic, Luxury, and the subtopic, what luxury means to different people.

Your dogs, like mine, think they ARE people. So the picture with one or more of your babies having luxurious drinks of clean water, while another celebrates his luxury soaking in the separate tub of clean water is a genius photo to include today.

And what a clever writer you are not to have belabored the point. You wisely let your readers see the photo and draw the same conclusion I did.

Bravo from Alabama!

I simply cannot Choose a room that’s my favourite as they were all amazing I felt so comfortable just struggling around soaking up the atmosphere it was wonderful and exceptional day out

Strolling not struggling

Good morning, Lady Carnarvon, from Surrey, British Columbia, Canada. Luxury is different things to different people as you say. Right now for me it’s relaxing in my housecoat with a lovely latte, reading your blog and not planning anything for this holiday Monday here! I so enjoy your Monday musings…..such a nice way to start the day. Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I look forward to visiting your beautiful home next September if all the stars align.

Judy

I hope they will align!

Lady Carnarvon,

Seeing the beautiful clock reminded me of the clock that Doc Martin was always trying to restore. I think, for me, my luxury is time. Spending time with the grandchildren, traveling, etc. Thank you for sharing your blog today.

Lady Carnarvon, such a meaningful story today. Luxury for me is nature and how it all surrounds me and my faithful and loving dog Anika. Luxury can be simple and pure and costs nothing. With Kind Regards, Cheryl.

I really do enjoy reading your latest blog, although I have not taken the time to comment until now. Many simple things are a luxury to me, and at the top of my list is reading a good book. Others are the spectacular views into the valley below from the east facing picture window of my simple country home. Early morning sunlight is the best view.

Thank you for the simple pleasure of reading your blog.

Carolyn rural Oregon

Thank you Carolyn

Your dogs are just so adorable! I love the picture of the lab in the troth and the picture of the sunset over the castle is magnificent.

Thanks again for a wonderful Monday morning journey.

The labradors just love a quick dip!

Well contemplated. I think this time period has cast a different light on what we consider “wants” and “needs.” The quote from Christian Dior (which places the physical needs of shelter, clothing, and food as all that’s essential for life–anything more is just icing on the cake) demonstrates what we typically understood as all that was “needed.” Yet, sadly, this pandemic has also highlighted mental and emotional needs through the way it has disrupted the normality of everyday life. Your writings are such a source of inspiration and example of how to “keep calm and carry on,” even when you’re figuring it out in the moment like everyone else. Thanks for pulsating out to the rest of us that beam of light to share your strength, wisdom, intellect, compassion, moxie, steadiness, and “flow.” And, of course, thanks also for sharing the beautiful Highclere Castle, grounds, history, and life with the world!

You are kind – there is no simple answer is there?

For the first time in reading your delightful blog I found a familiar spelling error.

Your clock is on the mantel, not the mantle….which is a cloth worn worn over the head or shoulders.

I have found this error in so many places even an LL Bean advertisement.

So now my work is done on this Labor Day.

Smiles always,

Nancy

Thank you !!!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I really enjoyed this story and especially the pictures of the dogs. You have a wonderful expressive gift in your writing. That in itself might be considered a luxury.

Sincerely,

Dianne Shanley

Very thought provoking.. I’ve had the luxury of indulging into creativity. Learned things never thought possible or the ability.

Barbara van Almelo Nelson

Beautiful dogs!

Dear Lady Carnavon,

Four years ago today, my sister and I spent the day wandering around Highclere and the grounds. We enjoyed tea there and had the opportunity to greet you. We were reminiscing about it yesterday and are yearning to return. We also had the great pleasure of enjoying dinner one evening there a couple of weeks before Christmas. We agree that evening was magical!

You are precisely correct to say that traveling has become an essential element of life. I look forward to visiting Highclere again. All the best, Christine Ayers

I enjoyed your “Luxury” blog today and what came to mind was that so many of us had the luxury of time during the pandemic shutdown. People were doing things they wished they had time to do, like painting, starting a garden or growing vegetables (moi aussi), doing house maintenance, sewing, or just read a book. I am happy that you have the time to write wonderful and interesting blogs to start off the week. I consider it a luxury to read them!

Aloha and blessings,

Ada

As a child in rural Kansas, I dreamed of travel to Europe, and especially the UK to explore my British roots. My family always told me I “ dream too big”. My husband and I have made the dream a reality. For the last 11 years, until the pandemic, we visited Europe each summer. For me, travel is a luxury to be savored!

Please keep writing! You have a gift!

Dear Lady Carnarvon:

Thank you for your Monday blog, sharing the Smoking Room, and the delightful pictures of the dogs (how funny).

How true, everyone seems to have their own definition of luxury. For me the meaning changed during last year’ s lockdown. What once was a luxury instantaneously became an “essential”, with no reversal to the prior definition.

Until next week, may you find some time to enjoy your favorite luxury.

Perpetua Crawford

Dear Lady Carnavon, like Ada, and others, I consider reading your blog a luxury. How dreary our lives would be without good writers! And the photos of your magnificent house, so interesting to see. I need not step out of my own life, to enjoy other lives, and since learning to read, it has always been my magic carpet. Please accept my thanks! What an interesting world we have. Best wishes, from faraway Texas.

I took my 101 pounds of chocolate lab for a short walk today. He was good….mostly. I’ve been working so much lately that a simple walk in the cool morning was delightful, just like your thoughtful post.

Yet again, I’m grateful to you for sharing the joys of your lovely home and surroundings.

MY DEAR LADY CARNARVON,

LUX? ? IT’S GETTING NEWS FROM HIGHCLERE CASTLE EVERY DAY.

THANK YOU VERY MUCH ,MILADY .

VILA ALEMÃ

RIO CLARO – SP

BRAZIL

Lady Carnarvon,

That is so true. Luxury is what we make of it. In the midst of all this. I hope one day we can dine, enjoy our friends and travel. For now I will keep enjoying my chamomile and lavender tea. These photos of your dogs are the best. They are cuddlely and cute.

Lady Carnarvon lovely pictures of luxury and pictures of dogs and lovely to visit highcelere castle and lovely downton abbeyfirst film cannot wait still the downton abbey second out and like get your blog

Lady Carnarvon lovely pictures of luxury and lovely first downton abbey movie and cannot wait to next downton abbey movie and lovely to visit highcelere castle