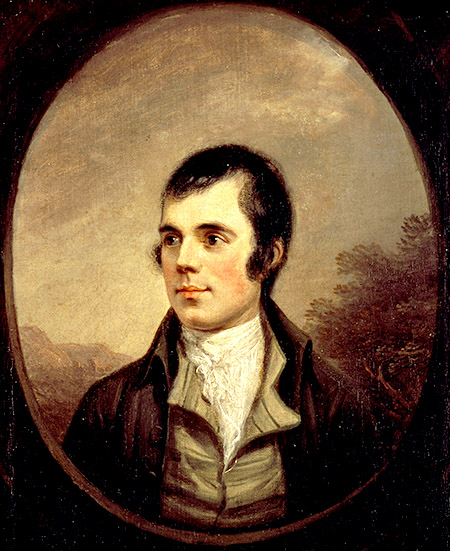

Shakespeare was born in England, Victor Hugo in France, Goethe in Germany, Dante in Italy and Yeats in Ireland. The list can go on and on but out of all the poets and authors, it is Robbie Burns from Ayrshire, Scotland whose work is sung around the world on New Year’s Eve and it is his birthday (January 25th) that is the only one that is celebrated every year both in, and far beyond the shores of, Scotland.

Shakespeare was born in England, Victor Hugo in France, Goethe in Germany, Dante in Italy and Yeats in Ireland. The list can go on and on but out of all the poets and authors, it is Robbie Burns from Ayrshire, Scotland whose work is sung around the world on New Year’s Eve and it is his birthday (January 25th) that is the only one that is celebrated every year both in, and far beyond the shores of, Scotland.

Being partly of Scottish heritage, and a graduate of St Andrews university, I of course persuaded Geordie that we should welcome a Burns party to Highclere. It has proved a high point of the annual calendar though last year of course it had to take place by zoom.

The evening has a lovely ritual, beginning with cocktails and reeling before processing into the dining room to the sounds of the piper, then the traditional menu and speeches and finishing with Auld Lang Syne.

At the heart of the evening is dinner with friends, exactly what we have all sorely missed for nearly two years. We begin with a little amuse bouche of haggis with “neeps and tatties”, before enjoying the traditional soup and main course, ending with Lord Carnarvon’s boozy bramble pudding. Between each course is a speech, the first of which is always the Ode to the Haggis whilst the second is a talk about Burns himself, a farmer’s son who was always broke and never travelled far from home.

Between each course is a speech, the first of which is always the Ode to the Haggis whilst the second is a talk about Burns himself, a farmer’s son who was always broke and never travelled far from home.

Burns’ education was minimal. He failed to make a living as a farmer and had a short and discouraging stint as a tax collector before briefly joining the army before succumbing to illness. He died, destitute and in debt, at just 37 years of age but at least was buried with full military honours. Despite this, Burns’ night celebrates a life lived to the full, of wine, women and song, that made him famous all over Scotland.

The tradition of Burns night was started by a young Burns in 1780 at the age of 21 when he and his brother Gilbert, along with some other young lads, founded the Tarbolton Bachelor’s Club as a: “diversion to relieve the wearied man worn down by the necessary labours of life.”

As its first President, Burns helped draw up the membership rules, one of which required that: ‘Every man proper for a member of this Society, must have a frank, honest, open heart; above anything dirty or mean; and must be a professed lover of one or more of the female sex’. He himself would most certainly be counted in the latter camp with many lovers to whom he wrote poems professing his affections.

Later Burns would publish a volume of the poems which he had written over a span of some years – the famous Kilmarnock edition of 1786. His style is marked by spontaneity, directness, and sincerity. His agrarian life gave him a close connection with nature which can be seen in many of his poems such as “To a Mouse” or “To a Mountain Daisy” and he collected and preserved folk songs from all over Scotland. As a storyteller poet, Burns has few peers: is there a better short ghost story than Tam o Shanter?

Later Burns would publish a volume of the poems which he had written over a span of some years – the famous Kilmarnock edition of 1786. His style is marked by spontaneity, directness, and sincerity. His agrarian life gave him a close connection with nature which can be seen in many of his poems such as “To a Mouse” or “To a Mountain Daisy” and he collected and preserved folk songs from all over Scotland. As a storyteller poet, Burns has few peers: is there a better short ghost story than Tam o Shanter?

In 1999, following devolution, the new Scottish Parliament opened with his poem “A Man’s a Man for a’ That” with its themes of equality and universal brotherhood whilst once more this week we shall sing together, here and around the world, a poem asking whether it is right that old times should be forgotten and which celebrates goodwill , good times and friendship:

In 1999, following devolution, the new Scottish Parliament opened with his poem “A Man’s a Man for a’ That” with its themes of equality and universal brotherhood whilst once more this week we shall sing together, here and around the world, a poem asking whether it is right that old times should be forgotten and which celebrates goodwill , good times and friendship:

“Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And days of auld lang syne.”

The tradition of singing the song, with crossed hands linked when parting, is such a strong symbol of being together and, wherever we live it is perhaps not surprising that it has such a universal place.

Instagram

Instagram

Thank you! Love this. We are having a Robert burns party tomorrow and I will take this to share!

I am sure it will be great fun!

What a evening! Even though my mother was a proud member of The Daughters of Scotia (Clan Cameron) I have to admit I have never eaten haggis & probably will go through my entire life without filling that void. However, I would love it if you could share the recipe for the Lord Carnarvon Boozy Bramble” it looked delicious.

It is quite long – it was one of the recipes in At Home at Highclere – maybe I can share it on instagram!

Loved this! A beautiful way to start my morning.

Thank you

Burns night here on Glasgow St was cancelled due to snow and ice storm. The wee drams surely survived!!

I hope so!

Thank you for your explanation of Burns Night. Now I understand! I know that a Burns Night party is one of the best celebrations one can attend, and I hope to do exactly that one year.

Do enjoy yours!

Sounds like alot of good fun. Wish I was there.

Great fun!

I initially read ‘Lord Carnarvon’s boozy bramble’ as Lord Carnavon’s boozy ramble! That aside, I have fond memories of a Burn’s Night with my friend’s military group. It was a fun night, with many a ‘boozy ramble’!

Fond memories of singing this with my family every New Years Eve. My Grandmother would play the upright piano and I would always have ginger ale in a champagne glass to toast.

It seems there was a depth to life back then. Even though there was hardship there was a lot of joy and celebration of living a simple life. A family gathering, the sound of a piper along with a warming fire and a table set brings comforting thoughts.

This was such a nice way to start the day. Thank you. Jo Makoul

Lovely memory

Monday morning Greetings from the USA Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you again for a lovely visual and beautifully written educational history lesson this morning! Given these days of the pandemic the verses of the song are appropriate to sing throughout the year and not just our New Years Eve. I am off to “take a cup o’ kindness yet for auld lang syne” with Monday Morning Ladies Coffee & Tea Gathering group.

Continue to remain well.

Enjoy your coffee gathering!

Thank you for this lovely post!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Wishing you all a wonderful celebration on the 25th…. I’m sure it will be wonderful on many levels!

Auld Lang Syne always brings tears to my eyes for the breadth of emotions it encompasses. A song for the ages.

Have great fun!

Best regards,

Charlotte Merriam Cole

It is a very emotional song

After reading your lovely post this morning celebrating Robbie Burns, I was inspired to learn more about him. So much sadness and hardship and longing and love and loss packed into such a short but brilliant life! I will think of him with fondness on January 25 from this day forward.

Extraordinary man

Thank you for your lovely tribute to Robert Burns and Burns Night. You’ve inspired me to re-read some of his poems. And maybe I’ll do so tomorrow night, on the 25th, with a glass of scotch in my hand!

Enjoy!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I love Haggis, Tatties and neeps, I love the sound of the boozy bramble pie, will you be putting the recipe on your page?

Wishing you a Happy Burns night

Regards

Lorraine xx

Thank you – it is a very easy recipe – as I mentioned above may be I can demonstrate on Instagram !

Lady Carnarvon lovely pictures of a cup of kindlessandyou and lord carnvaron a nice weekend and l would love to visit highcelere castle

Hello Lady Carnarvon

Do you say “Welcome to ma hoose. The drinks are o’er there.”

At Battle Proms, the arena goes crazy when Lang Syne is performed at the end of the evening.

One year, a party of Scots in the audience were playing the pipes while everyone was leaving.

Another year, a solo piper performed on stage and later played Lang Syne and Black Bear for those leaving.

Who will be addressing the the haggis at Highclere.

When I was working, the restaurant manager always arranged to have a piper performing in the atrium. Were you there then?

Carry on celebrating.

As always, beautifully written with so much history added. Thank you for sharing this with us.

J. Davies

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

how wonderful to hear about parties again! Burns night is wonderful way to cheer up a dreary January after Christmas has been packed away, and the Scots certainly know how to party! I’ve got a Scottish reel playing in my head now lol!

Kind regards,

Jane Bentley

As always, a welcomed treat on a Monday morning!

I have heard of your Burns party for many years now and it sounds like such a magical evening. I can only imagine John’s rendition of “Ode to the Haggis” as being one of the highlights of the evening. He is such a character, I’m sure it is quite entertaining!

Wishing you the happiest and merriest for your Burns party this year!

Patsy

Thank you Patsy!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you for today’s post. I enjoyed learning more about Robert Burns and how you celebrate. I know fun was had by all.

To more merriment this coming year,

Pam

Absolutely!

Dear Lady Carnarvon, God Bless Dear Robbie Burns, he should be with us now, and we should be holding hands, and singing Auld Lang Syne, throughout this whole pandemic, not just once a year. Thank you for sharing, as always, brilliant. Desiree Creary.

Thank you once again for reminding us how special the Burn’s Night Parties are.

Hoping by 2023 we can gather again “in person” to enjoy this tradition.

Wendy (Glengarry County Canada)

Tomorrow is my oldest’s bday as well!! Lily Frances will turn 23 tomorrow, and I am happy to have this info to share with her! Thank you for sharing!! ❤️

Happy Birthday Lily

Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you sincerely for the lovely explanation of the importance of Robert Burns’ writings.. As an American named for her 10-year-old deceased aunt Bonnie Andrews, who died in Louisiana during the last big pandemic (Spanish flu, 1918), I fully appreciate today’s Cup O’ Kindness.

Thank you also for the exceptional photographs taken around your home. Your arrangement of mixed flowers is one of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen! And what better way to start a Monday morning than with snaps of beloved doggos under a desk.

Again, thank you kindly for sharing your knowledge and your gracious home.

Thank you!

A lovely topical blog. I believe a little “Scottish gravy” (whisky of course) is in order on Burns night along with the Haggis.

Auld Lang Syne is a beautiful song, bringing back special memories of New Year’s Eve in years gone by.

Have fun at your Burns night party.

Thank you Joan

PS. Your beautiful labradors look as if they’re waiting patiently and already sniffing the Haggis1

Lady Carnarnvon,

I can hear the piper’s lovely strains pouring forth “Auld Lang Syne.” Thank you for another reminder of our Scottish heritage and young Robert Burns. Just goes to show that one doesn’t have to live a long life to make a very measurable mark on history! Bless his heart.

Martha G.

How true!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you for taking me back to such fond memories. Every time I visit Scotland I have the haggis. We have a breakfast meat called scrapple here on the east coast of America that reminds me of the haggis.

You gave me a theme for our small party this weekend that we put off on New Years Eve.

Regards,

Linda Kaempf

Excellent!

Dear Lady Carnarvon and bloggers,

Sláinte Mhath.

It sounds like you have planned a splendid Burns Night. Unfortunately I just can’t force myself to eat haggis. (I believe it’s import into the US is illegal.)

However, the multiple varieties and vintage of fine whiskies (‘Scotch’) are a different story and there is other fare that is palatable, if not strictly traditional.

I assume that, as host, your husband Geordie will be giving the Selkirk Grace. Will he also be giving the “Address to the Lassies” and/or will you be giving ‘The Reply’?

Have a wonderful night and in these still difficult times, celebrate not only Burns and his poetry but also the joy and camaraderie of being with good friends and happy times.

Regards,

Jeffery Sewell

Thank you Jeffery

Lovely to see your comments again in Lady Carnarvon’s Monday Family posts, Mr. Sewell!

Kindest regards,

HveHope

Wonderful reminder of an event in which we can all share. Thanks for the information of the Burns’ Night Party. Please publish the Bramble recipe. I have quite a few of your blogs to read; life has been a bit demanding for awhile. I’ve missed your writings. Happy New Year! Ida

How kind thank you!

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you for your reminder of the beauty of Robert Burns’ poetry. I taught British Literature and Burns’ poem, “To a Mouse” was always a favorite. There are so many insights for us including living in the present, taking care of our animal friends, and not counting on everything happening according to plan, “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft agley.” You certainly have lived that out at Highclere. Enjoy your celebration!

It is my birthday tomorrow as well. As a teacher of English as a foreign language I always try to find time to tell my students about Robert Burns and Auld Lang Syne. Thank you for all the information.

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Another lovely blog. Really enjoyed this as it brought back so many wonderful memories. I received your latest book Seasons at Highclere, and have gotten lost in it…Thank you for all my entertainment during this pandemic!

Thank you – So glad you are enjoying Seasons at Highclere

Lady Carnarvon, Perfectly wriiten and a joy to read. All the best on Robbie Burns’ Night. Cheryl

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

I’ve just finished ready about your New Years Eve celebration in your book Christmas at Highclere. Such fun! I for one think it marvelous that you’ve incorporated your Scottish heritage into Highclere. What a delicious book, I’ve read it cover to cover many times over and recommend it to everyone! Thank you.

Wishing you a fabulous Burns Night!

Kind regards,

Pamela Steinhauser

How very kind thank you

Lady Carnarvon,

Thank you for the preview of what you will be celebrating tomorrow evening. Just a couple years back my wife and I visited the Burns Museum which is luckily for Americans beside the bridge over the River Doon (we think of the lovely movie Brigadoon). We enjoyed everything about the complex in Alloway the Poet’s Path, the gardens, artifacts and exhibits.

Some of my friends celebrate Mr. Burn’s birthday and drinking copious quantities of beer whilst individually reading their own favorite Burns poem.

I wish you success on the festivities tomorrow.

Hi!

Really interesting story as always!

I have thought about buying one of your books and the choice is between Lady Almina and Lady Catherine if I have understood right has Lady Almina has more parallels to Downton Abbey than Lady Catherine has. Are there any more differences and which one do you recommend the most?

Both of course – start with Almina! Amazon has them

Ok, thanks! Of course, will I buy them both!

The Scot in me had me running for the Burns…The “boys” appear ready for any droplets…. Thank you for reviving favorite memories! Donna from Boise

Lady Carnarvon with the very appropriate Scottish christian name 🙂

My mother was born in Broughty Ferry, Dundee and came to Australia as a wee three year old who was always Scottish to her boot straps until she died. Her mother never lost her accent although it mellowed and had Australian words creep in and she was always Scottish to her boot straps as well and that heritage continues on with my daughter named Heather and grand-daughter Leith.

I can remember going “first footing” at Hogmanay, Burns Night Dances with the Eighthsome Reel and such, lots of whooping and singing until the wee hours and all of us children sleeping on the floor of the dance hall. Learning to speak “Scottish” included “t’s a braw bricht moonlicht nicht the nicht”, “Ah dinnae ken” and “Long may ya lum reek”(which means its a broad bright moonlight night tonight, I don’t know and long may your chimney smoke). Singing Scottish songs at parties was compulsory in our household and I have fond memories of Ye Banks and Braes and Roamin’ in the Gloamin etc. I think I had a well rounded education so long as it was something Scottish LOL.

So have a great Burns Night with all the traditions associated with it, enjoy a “wee dram of whusky”, praise the Haggis and dance and sing to celebrate. Wee Rabbie Burns would be proud of ye.

Joy

Orange, Australia

I love the reeling too -such fun dances

Lady Carnarvon,

How utterly fascinating and fun! Reading your colorful stories which you paint so beautifully with words, I can feel like I’m am right there in the midst of the celebrations!

Most Sincerely,

Gay Hightower.

Our name means “GOD IS A TOWER OF STRENGTH TO ME” from the Latin motto, TURRIS MIHI DEUS.

Thank you for another very informative blog. I love that your two labs are front and center in such an adorable photo. That must have been an awkward position to take the photo! Usually when I hear bagpipes in Hawaii, they are played at somber events, such as funerals or observance days. But when I heard it played in Scotland and England, it was a delight to hear. Singing Auld Lang Syne always brings on a reflection of the past year and hopes for the new year, especially in these times. Wishing you continued good health and prosperity (and, hopefully, Downton Abby #3)!

I love bagpipes – they will be on the instagram tomorrow!

Please drink a hearty toast to my Scottish ancestors!

Tho’ my Wallace ancestors ended up in Bushmills Northern Ireland…

And I gave up strong drink 25 years ago.

Wallace Craig

Midland Texas

Being Australian, today is the 25th already and so, tonight we are off to a Burns night put on by a Scottish friend for his friends of Scottish ancestry. We are Scottish on all sides but 8 generations removed to Australia. It is lovely to have some connection to our ancestral culture. It will be a night of haggis, tatties and neeps with ‘sauce’, a cranachan for dessert, the Ode, and lots of singing lubricated by whisky! Despite the predicted 30 plus degree summer temperatures, the men will be wearing their kilts though not a jacket!

Thank you for that wonderful history. I had no idea that he died so young.

Like most other commentators, I would also love the boozy bramble pudding. We are picking some bramble berries today and will bring them along to have with the cranachan.

Have fun!

So many memories of past Burns Suppers here in Houston, Texas, put on by The Heather & Thistle Society for fifty years. My late husband, who originates from Aberdeen, Scotland, was very active in these suppers, giving the Address to the Haggis on many occasions. We had some incredible speakers of the Immortal Memory over the years and the one I remember above all others was given by Tom Sutherland, Dean of Agriculture at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon who was kidnapped by Islamic Jihad members back in 1985. He was released the same time as Terry Waite after six years in captivity. Tom was from Falkirk and he said it was by reciting Robbie Burns and the Bible that kept him sane throughout his captivity. You could hear a pin drop in the hall as we held on to every word he spoke. He lived in Colorado and died in Fort Collins, Colorado in 2016 at age 85. A truly remarkable man who loved Burns. Thank you for your lovely story.

Burns lived to the full despite the challenges

Lady Carnarvon,

It is now January 25th here in Virginia and we wish Robbie Burns a Happy Birthday in Heaven and a heartwarming, finally in-person, celebration to you all at Highclere Castle and to those everywhere around the world who celebrate him.

So tonight, we shall be thinking of you all as we too will “tak a cup o’ kindness yet…

For auld lang syne.”

We eagerly look forward to your posting on Instagram.

Thank you both – it is everything we could not do for two years that matters so much expressed in those few words…

Wow I just love your wonderful stories so informative and always make me smile

Lady Carnarvon,

Love this story of poetry. I always listen to this song and waltzes in December. One of my favorites.

Dear Lady Carnarvon, Thank you for a lovely memoir. It was cheery in such a wearisome time !

Dear Lady Carnarvon,

Slàinte Mhath

Good Health to you too!

January 27, 2022

Dear Lady Carnarvon!

How I loved to read about your Great January party! I also enjoy The wonderful book “Christmas at Highclere”. It is such a fantastic and inspiring book and I love to watch The beautiful photos and read everything. As a matter of fact I already Long for next Christmas!

Have a Nice Day!

Swedish greetings from Lena

Dear Lady Carnarvon:

Thank you for your Monday blog.

Hope you enjoyed your (Robert) Burn’s night on January 25.

I was unable to reply sooner, as my youngest brother has been in the hospital. A cup of kindness sure could be used right about now.

Until next Monday, stay healthy and safe.

Perpetua Crawford